|

IN THE NEWS

THE NEW YORK TIMES

May 21, 2018

Richard N. Goodwin, Adviser to Democratic Presidents, Dies at 86

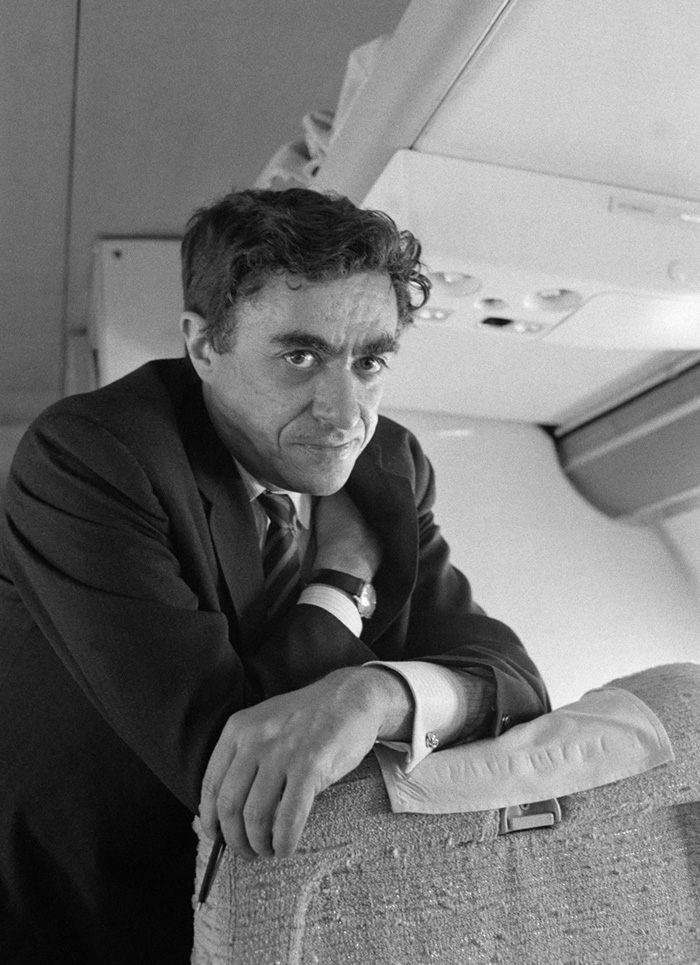

Richard N. Goodwin, a senior adviser and speechwriter for Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson whose later work as an author, journalist and political consultant reflected his unswerving liberal outlook, died on Sunday at his home in Concord, Mass. He was 86.

Mr. Goodwin’s wife, Doris Kearns Goodwin, the Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer and historian, said he died after a brief bout with cancer.

The author of books and articles on public policy and a play, Mr. Goodwin was for years identified with the Kennedy clan and with leaders of the Democratic Party.

In 2000 he helped write the concession speech that Vice President Al Gore delivered after the Supreme Court halted the Florida recount in the presidential election, effectively handing the White House to George W. Bush. In 2004 he was a campaign consultant for the Democratic presidential nominee, Senator John Kerry of Massachusetts, and in 2008 Barack Obama consulted him in his presidential campaign.

Mr. Goodwin called himself a voice of the 1960s, and with justification. He had written many of the memorable campaign and Oval Office speeches of the period, capturing the soaring hopes and lost dreams of two Democratic presidents, two senators who ran for the presidency and a nation caught up in nuclear perils, civil rights struggles, assassinations and divisions over the war in Vietnam.

In the Kennedy White House from 1961 to 1963, he specialized in Latin American affairs and was instrumental in creating the Alliance for Progress, an economic cooperation initiative between North and South America, which he named. He was deputy assistant secretary of state for Latin American affairs and directed the International Peace Corps, developing similar programs in other countries.

After Kennedy’s assassination, Mr. Goodwin joined the Johnson administration, advising the new president on domestic policies and writing many of his speeches, including one that outlined his signature legislative agenda, “the Great Society,” a phrase he coined, and an address to the nation that affirmed Johnson’s commitment to the civil rights movement and reiterated the words of its anthem, “We shall overcome.”

“Dick Goodwin was a lion of liberalism before it became a dirty word, crafting speeches for Democratic icons that define the politics and progressivism of the 21st Century,” Mark K. Updegrove, the president and chief executive of the LBJ Foundation, said in an email. “His ‘We Shall Overcome’ speech, L.B.J.’s plea for the Voting Rights Act in the wake of Selma’s ‘Bloody Sunday’ resulting in direct action from a formerly reluctant Congress, ranks as one of the most eloquent and effective presidential speeches in history.”

Mr. Goodwin helped draft the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965, which outlawed literacy tests and other discriminatory practices that had long disenfranchised black Americans. For a time, as Mr. Goodwin later recalled, he deeply believed in Johnson because of his work for civil rights and social reforms.

But as the administration’s involvement in Vietnam grew, Mr. Goodwin left in 1965 and began to write and speak against the war. In 1968, after Johnson announced that he would not seek re-election, Mr. Goodwin became an adviser and speechwriter in the Democratic presidential campaigns of Senators Robert F. Kennedy of New York and Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota, both staunch opponents of the war.

Mr. Goodwin was with Robert Kennedy in Los Angeles when the senator, after winning the California primary, was fatally shot by an assassin. He was then McCarthy’s speechwriter, until the Democrats nominated Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey at a Chicago convention overshadowed by clashes between the police and antiwar protesters.

Brilliant, intense, sometimes abrasive, Mr. Goodwin had the look of a rumpled professor. He smoked big cigars, favored turtlenecks and corduroy jackets and had long, shaggy hair. His voice was gravelly and slightly slurred, his face craggy, with silver-gray eyebrows that jutted up devilishly.

He taught at Wesleyan University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and wrote for Rolling Stone, The New Yorker, The New York Times and other publications. His books included “The Sower’s Seed: A Tribute to Adlai Stevenson” (1965), “Triumph or Tragedy: Reflections on Vietnam” (1966), “The American Condition” (1974) and “Promises to Keep: A Call for a New American Revolution” (1992).

His memoir, “Remembering America: A Voice From the Sixties” (1988), stirred controversy with a portrayal of President Johnson as erratic, isolated, even paranoid. Some who had known Johnson disputed Mr. Goodwin’s conclusions. Critics praised his passionate liberal assessment of the era, but said he ignored many scholarly and political re-evaluations of the 1960s.

Richard Naradof Goodwin was born in Boston on Dec. 7, 1931, one of two sons of Joseph and Belle Fisher Goodwin. Dick and his younger brother, Herbert, grew up in Brookline. Dick was first in his class at Tufts University, graduating in 1953, and in Harvard Law School’s class of 1958. He was a clerk for Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter of the Supreme Court for a year. His brother, a Massachusetts district court judge in Brookline for many years, died in 2015.

In 1958 he married Sandra Leverant, with whom he had a son, Richard. She died in 1972. He married Doris Kearns in 1975. They had two sons, Michael and Joseph. Besides his wife and sons, he is survived by two granddaughters.

In 1959, Mr. Goodwin joined the staff of a House subcommittee investigating rigged television quiz shows. Part of “Remembering America” focused on the scandals and was a basis for the 1994 film “Quiz Show,” which he helped produce. His work impressed Robert Kennedy, and he was enlisted for Senator John Kennedy’s staff. He and Theodore C. Sorensen wrote most of Kennedy’s presidential campaign speeches.

Mr. Goodwin’s play, “The Hinge of the World,” on the struggle during the Inquisition between Pope Urban VIII and Galileo, who was accused of heresy for arguing that the earth was not the center of the universe, had its premiere in Guildford, England, in 2003. It was produced in Boston in 2009 as “Two Men of Florence.”

“Richard Goodwin’s talent as a playwright was unique,” Edward Hall, who directed both productions of the play, said in an email. “He had the rare ability to take huge ideas and render them into human drama. Being in a rehearsal room with Richard will remain a highlight of my career. His characters were enriched by an author who blended a lifetime’s experience of working close to power, with a deep understanding and care of humanity.”

Al Gore’s presidential concession speech in 2000, written by Mr. Goodwin, quoted Senator Stephen Douglas’s concession to Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 presidential election: “Partisan feeling must yield to patriotism.”

Mr. Gore’s speech went on: “Just as we fight hard when the stakes are high, we close ranks and come together when the contest is done. And while there will be time enough to debate our continuing differences, now is the time to recognize that that which unites us is greater than that which divides us. While we yet hold and do not yield our opposing beliefs, there is a higher duty than the one we owe to political party. This is America, and we put country before party; we will stand together behind our new president.”

THE WASHINGTON POST

May 21, 2018

Richard N. Goodwin, ‘supreme generalist’ who was top aide to JFK and LBJ, dies at 86

Richard N. Goodwin, a top adviser and speechwriter to Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson who was credited with coining the term “the Great Society” to describe Johnson’s ambitious domestic agenda of the 1960s before parting ways with the president over the Vietnam War, died May 20 at his home in Concord, Mass. He was 86.

The cause was complications from cancer, said his wife, Pulitzer Prize-winning presidential historian Doris Kearns Goodwin.

Early in his career, Mr. Goodwin was something of a prodigy of public service. Before he turned 30, he was a law clerk at the U.S. Supreme Court, a congressional investigator who helped uncover the television quiz-show scandals of the 1950s, a speechwriter for Kennedy, a White House official and a deputy undersecretary of state.

Known for his craggy face, blunt manner and ever-present cigars, Mr. Goodwin had a sharp mind — he was first in his class at Harvard Law School — and, some would say, sharper elbows. He was considered one of the closest confidants of Kennedy and his brother Robert F. Kennedy, then the attorney general.

In his book “A Thousand Days,” about Kennedy’s presidency, historian and White House adviser Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. pronounced Mr. Goodwin “the supreme generalist who could turn from Latin America to saving the Nile Monuments, from civil rights to planning a White House dinner for the Nobel Prize winners, from composing a parody of Norman Mailer to drafting a piece of legislation, from lunching with a Supreme Court Justice to dining with [actress] Jean Seberg — and at the same time retain an unquenchable spirit of sardonic liberalism and unceasing drive to get things done.”

During the 1960 presidential campaign, Mr. Goodwin worked alongside head speechwriter Ted Sorensen as one of Kennedy’s most gifted phrasemakers. He then became the top White House authority on Latin America and launched the Alliance for Progress, an economic development program for Central and South America.

In 1961, soon after the catastrophic, American-backed Bay of Pigs invasion that attempted the overthrow of the new socialist regime of Fidel Castro in Cuba, Mr. Goodwin had a secret meeting with Ernesto “Che” Guevara, an architect of the Cuban revolution, while both were in Uruguay to ratify the Alliance for Progress.

“But, of course, when we started this conversation though, he said, ‘Mr. Goodwin, I’d like to thank you for the Bay of Pigs,’ ” Mr. Goodwin recalled in a 2007 gathering at the John F. Kennedy library in Boston. “He said, ‘We were a pretty shaky middle class, support was uncertain, and this solidified everything for us.’ So what could I say? I knew he was right.”

Over the objections of State Department diplomats, Mr. Goodwin arranged a goodwill tour by Kennedy to South America, which turned out to be a resounding success. Mr. Goodwin later moved to a top position at the newly formed Peace Corps.

A New York Times profile announcing yet another appointment for Mr. Goodwin as the White House adviser on the arts described him as “someone whom the President turns to naturally and with a sense of intimacy.”

The profile appeared on Nov. 22, 1963, the day Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. Mr. Goodwin never assumed his role as arts adviser and, instead, joined the Johnson administration as a speechwriter and special assistant to the president.

In April 1964, Mr. Goodwin recalled in a 1988 memoir, “Remembering America: A Voice From the Sixties,” he found himself skinny-dipping in the White House swimming pool with Johnson and another presidential adviser, Bill Moyers.

“Now, some men want power so they can strut around to ‘Hail to the Chief,’ ” Mr. Goodwin recalled Johnson saying as they splashed in the pool. “Some . . . want it to make money; I wanted power to use it. And I’m going to use it. And use it right if you boys’ll help me.”

Mr. Goodwin took the name the Great Society from a 50-year-old book by a British sociologist to describe an idealistic vision of America encompassing advances in civil rights, health care, education, environmental preservation and what became known as “the War on Poverty.” Johnson first used the term “Great Society” in a speech in May 1964.

The following year, soon after civil rights marchers were attacked by police officers and vigilantes on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., Johnson asked Mr. Goodwin to draft a speech addressing the country’s racial divisions.

In just eight hours, Mr. Goodwin composed an address that Johnson delivered before a joint session of Congress on March 15, 1965. Often called the “We Shall Overcome” speech, after a popular civil rights anthem, it was one of the most powerful statements of Johnson’s presidency.

“Our mission is at once the oldest and the most basic of this country: to right wrong, to do justice, to serve man,” Johnson said. “What happened in Selma is part of a far larger movement which reaches into every section and state of America. It is the effort of American Negroes to secure for themselves the full blessings of American life. Their cause must be our cause too. Because it is not just Negroes, but really it is all of us who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome.”

After the speech, Mr. Goodwin returned with Johnson to the White House, where they sat up talking and sipping Scotch until 3 a.m. At 33, Mr. Goodwin had, in many ways, reached the summit of his career.

Sitting with LBJ, he “could indulge, inwardly, my mingled arrogance, pride, excitement at authorship of words that had touched, might change, the nation,” he later wrote.

Within months, Johnson signed the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965, which banned discrimination in voting and office-seeking in the United States. He gave one of the pens he used to sign the bill to Mr. Goodwin.

In addition to the Voting Rights Act, other Great Society legislation established Medicare, Medicaid, Head Start, urban renewal programs and national endowments for the arts and humanities. At the same time, however, Johnson was escalating the U.S. military presence in Vietnam, leading to an irreparable split with Mr. Goodwin, who resigned in September 1965.

The next year, he helped Robert Kennedy craft a memorable address in South Africa in which he condemned the apartheid system and warned against the “danger of futility: the belief that there is nothing one man or one woman can do against the enormous array of the world’s ills. . . . Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lots of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring, those ripples build a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.”

That same year, Mr. Goodwin also published a book critical of the Vietnam War, “Triumph or Tragedy.” Under an assumed name, he wrote several articles for the New Yorker magazine denouncing Johnson’s Vietnam policies. He also represented Jacqueline Kennedy in a legal battle over perceived invasions of privacy in William Manchester’s book “The Death of a President.” Portions of the manuscript were deleted, and tapes of Manchester’s interviews with the widowed first lady were sealed for 100 years.

In 1968, he wrote speeches for antiwar presidential candidate Sen. Eugene J. McCarthy (D-Minn.). But when Robert Kennedy entered the race, Mr. Goodwin joined his old friend, saying he could not “campaign to defeat a man I’ve eaten dinner with once a week for these many years.”

After Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles in June, Mr. Goodwin rejoined McCarthy, who lost the nomination to Sen. Hubert H. Humphrey (D-Minn.).

Mr. Goodwin later remarked that a decade that began with the youthful promise of John F. Kennedy’s election ended in sorrow and despair.

“For a moment, it seemed as if the entire country, the whole spinning globe, rested, malleable and receptive, in our beneficent hands,” Mr. Goodwin wrote in his memoir. That sense of hope “came to an end in a Los Angeles hospital on June 6, 1968,’’ with the death of Bobby Kennedy.

Richard Naradof Goodwin was born Dec. 7, 1931, in Boston. His father was an engineer, his mother a homemaker. Mr. Goodwin said his Jewish heritage sometimes led to schoolyard beatings during his childhood.

He graduated in 1953 from Tufts University in Medford, Mass. After two years in the Army, he received his law degree from Harvard in 1958. He clerked for Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter and then worked for a U.S. House committee investigating corrupt television quiz shows, particularly “Twenty One,” on which literary scholar Charles Van Doren was given answers in advance and won more than $100,000 in prize money.

Mr. Goodwin wrote about the investigation in his memoir “Remembering America,” which formed the basis of the Oscar-nominated 1994 film “Quiz Show,” directed by Robert Redford. Mr. Goodwin was portrayed by actor Rob Morrow.

Mr. Goodwin’s first wife, Sandra Leverant, died in 1972. Survivors include his wife of 42 years, Doris Kearns Goodwin of Concord; a son from his first marriage, Richard Goodwin; two sons from his second marriage, Michael Goodwin and Joseph Goodwin; and two granddaughters.

In 1988, Mr. Goodwin stirred up controversy when he wrote in “Remembering America” about what he called Johnson’s “sporadic paranoid disruptions” that affected the president’s judgment, particularly about Vietnam.

He was “convinced that President Johnson’s always large eccentricities had taken a huge leap into unreason,” but other longtime White House insiders, including former secretary of state Dean Rusk, derided such speculation as “nonsense.”

Mr. Goodwin was the political editor of Rolling Stone for a short time in the 1970s and published several other books, including “The American Condition” (1974) and “Promises to Keep: A Call for a New American Revolution” (1992). He also wrote a play about the 17th-century dispute between the scientist Galileo and Pope Urban VIII.

After 1968, Mr. Goodwin largely stayed out of the fray of electoral politics, but he did write one other memorable speech — Al Gore’s concession after the disputed presidential election of 2000.

In his final years, Mr. Goodwin was seen as one of the last links to the Camelot era of the Kennedys. It was never too late, he wrote in his memoir, to “pick up the lost instruments and resume the great experiment which is America.”

MSNBC

22 May 2018

Author & Political Aide Richard Goodwin Dies At 86

THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER

25 May 2018

Richard Goodwin, Presidential Speechwriter and Author, Dies at 86

Richard N. Goodwin, author, playwright, and presidential speechwriter whose role in the Congressional quiz show investigation of the late ‘50s inspired the Oscar-nominated movie 'Quiz Show,' dies at 86.

Richard N. Goodwin, the author, playwright, political adviser and presidential speechwriter whose role in the Congressional quiz show investigation of the late 1950s inspired the Oscar-nominated movie Quiz Show, died peacefully May 20 after a brief bout with cancer at his home in Concord, Massachusetts. He was 86.

Goodwin first worked at the White House at age 29 as an aide to President John F. Kennedy, on whose campaign he’d worked as a speechwriter. He served as Assistant Special Counsel to the President and as a key specialist on the Task Force on Latin-American affairs. He also served as Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs, and was Secretary-General of the International Peace Corps. After Kennedy’s assassination, Goodwin became Special Assistant to President Lyndon B. Johnson, formulating the concept of the Great Society and drafting many of Johnson’s major civil rights addresses.

As a speechwriter, Goodwin also authored Kennedy’s Latin American speeches, Sen. Robert Kennedy’s “ripple of hope” speech in South Africa in 1966 and, most famously, Johnson’s 1965 civil rights speech, which came to be known as the “We Shall Overcome” speech, delivered on March 15, 1965, to a joint session of Congress. That speech led to the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that Johnson signed five months later.

Historian Arthur M. Schlesinger described Goodwin as an “archetypal New Frontiersman” in his book A Thousand Days, writing, “Goodwin was the supreme generalist who could turn from Latin America to saving the Nile Monuments, from civil rights to planning a White House dinner for the Nobel Prize winners, from composing a parody of Norman Mailer to drafting a piece of legislation, from lunching with a Supreme Court Justice to dining with [actress] Jean Seberg — and at the same time retain an unquenchable spirit of sardonic liberalism and unceasing drive to get things done.”

Resigning from the White House in 1966 to join the anti-war movement, Goodwin briefly directed Eugene McCarthy’s presidential campaign in New Hampshire and Wisconsin and wrote speeches for presidential candidate Edmund S. Muskie before joining Robert Kennedy’s presidential campaign, and he was with Kennedy in Los Angeles when Kennedy was assassinated in 1968.

Goodwin was the author of four books including The American Condition, Promises to Keep: A Call for a New American Revolution and his memoir, Remembering America: A Voice From the Sixties, which was rereleased in e-book format in July 2014.

In Remembering America, Goodwin recounted his experience as special counsel to the Legislative Oversight Subcommittee of the U.S. House of Representatives, during which he conducted the now well-known investigation of the Twenty One quiz show scandal. His story was the basis for Robert Redford’s 1994 film, Quiz Show, in which Goodwin was portrayed by actor Rob Morrow. The film itself was nominated for four Academy Awards, including best picture.

Goodwin’s play The Hinge of the World, a drama about the confrontation between Galileo Galilei and Pope Urban VIII, published by Farrar Straus & Giroux, has been performed at the Yvonne Arnaud Theatre in Guildford, England, and at the Huntington Theatre in Boston, where it was retitled Two Men of Florence. The play has been adapted by screenwriter Alyssa Hill for a feature film now in development at Warner Bros.-based Gulfstream Pictures.

Goodwin, who graduated summa cum laude from Tufts University and from Harvard Law School, served as a law clerk to U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter before being appointed as special counsel to the congressional subcommittee on which he worked. His many awards and honors include the John F. Kennedy Library Distinguished American honor, the Aspen Institute’s Public Leadership Award and honorary degrees from Tufts, UMass Lowell and Hebrew Union College.

Goodwin is survived by the Pulitzer Prize-winning presidential historian Doris Kearns Goodwin, his wife of 42 years; their sons Michael and Joseph; his son Richard from a previous marriage; and two granddaughters, Willa and Lena.

A memorial will be held June 15 at the First Parish in Concord. In lieu of flowers, contributions may be made in Goodwin’s name to the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute to support head and neck research and care, 10 Brookline Place West, 6th Floor, Brookline, MA 02445 or online at danafarbergiving.org.

THE BOSTON GLOBE

29 March 2017

Democracy teeters on the income gap

"Former President Barack Obama this week designated income inequality and lack of social mobility “the defining challenge” of our time. I am in accord; indeed, evidence of this “defining challenge” appeared on the horizon long before the widespread attention it is currently receiving. More than three decades ago, I wrote the following op-ed for the Los Angeles Times. Though recent statistics reveal an even greater hardening of class division and income inequality, I’d like to believe that the optimistic pulse of what I wrote in 1985 – that problems devised by us can be resolved by us – still resonates. For if we abandon the struggle for economic justice we will have abandoned our essential allegiance to the great experiment that is America," wrote Richard N. Goodwin in today's The Boston Globe. Read the rest of the column here.

THE BOSTON GLOBE

25 May 2016

Hollywood plans feature film based on Dick Goodwin play

With an eye toward turning the play into a feature film, Hollywood’s Gulfstream Pictures has acquired the rights to Dick Goodwin’s historical-philosophical drama, “The Hinge of the World.” Gulfstream partners Mike Karz and Bill Bindley announced the deal Wednesday. Goodwin (inset), who lives in Concord with his wife, presidential historian Doris Kearns Goodwin, said he’s delighted. “I’m very pleased. Wouldn’t you be?” Goodwin joked. “I worked very hard writing this play and I love the idea.”

VARIETY

25 May 2016

Richard Goodwin’s Play ‘Hinge of the World’ to Be Adapted Into Movie

Gulfstream Pictures has acquired the feature film rights to Richard N. Goodwin’s play “The Hinge of the World,” which centers on the battle between Galileo and the Pope.

The play was published in 1998 with the title “The Hinge of the World: In Which Professor Galileo Galilei, Chief Mathematician and Philosopher to His Serene Highness the Grand Duke of Tuscany, and His Holiness Urban VIII Battle for the Soul of the World.”

THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER

25 May 2016

Gulfstream Pictures Acquires Rights to Richard N. Goodwin's Play About Galile

'The Hinge of the World' is the first play by Goodwin, whose book 'Remembering America' was the basis for the film 'Quiz Show.'

Gulfstream Pictures has acquired the feature film rights to Richard N. Goodwin’s play The Hinge of the World, which focuses on the clash between astronomer Galileo Galilei and Pope Urban VIII, it was announced Wednesday by Gulfstream partners Mike Karz and Bill Bindley.

Goodwin’s play explores the science, faith and politics as it depicts how Galileo tried to convince the 17th century pope that Earth was not the center of the universe.

“The battle between Galileo and Pope Urban really plays out in an exciting and intriguing way, with the earth's true place in the world hanging in the balance,” Bindley said in announcing the deal.

DEADLINE.COM

25 May 2016

Richard Goodwin’s ‘The Hinge Of The World’ About Epic Clash Between Church And Galileo Being Developed As Feature

BREAKING: Richard Goodwin’s play The Hinge of the World which tells the story about the epic battle between the Roman Catholic Church and astronomer Galileo Galileo when faith clashed with science is being developed for the big screen by Mark Karz and Bill Bindley’s Warner Bros.-based Gulfstream Pictures.

PBS documentary "JFK & LBJ: A Time for Greatness"

8 August 2015

As the country celebrates the 50th Anniversary of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s signing of the Voting Rights Act, Richard N. Goodwin reflects in the new PBS documentary "JFK & LBJ: A Time for Greatness" on the seminal "We Shall Overcome" speech that he wrote for LBJ. The now immortal words captured the historical sweep of black Americans from slavery to true freedom. Hear Goodwin's recollections of that momentous time here.

CHICAGO READER

3 June 2015

Fifty years after LBJ challenged the nation, the rights of African-Americans remain unfulfilled

THE WASHINGTON POST

31 January 2015

'Selma' and celebrating an American triumph

by Richard N. Goodwin

Richard Goodwin served as a special assistant and speechwriter for President Lyndon Johnson.

The continuing wrangles over the movie "Selma" - contention over the relative roles played by Martin Luther King Jr., the civil rights movement, Lyndon B. Johnson and the federal government - miss the essential point: In the spring of 1965, the Selma demonstrators and the president of the United States forged an authentic partnership that ultimately resulted in the passage of the Voting Rights Act. The act guaranteed the right to vote to millions of African Americans. This historic landmark was realized because the pressure from the outside brought to bear on our ruling authorities was fully embraced by the government.

On March 7, 1965, a day forever known as "Bloody Sunday," peaceful demonstrators were savagely attacked by local police on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. The brutal images that flashed across the television screen provided a sense of urgency to the issue of voting rights. Eight days later, on March 15, I reached my White House office in the morning and learned that I was to work on the speech President Johnson was to deliver that evening to a joint session of Congress, urging the immediate passage of the Voting Rights Act. There was no argument to be weighed in this speech. There was no debate, one side against the other. There was only one side and one position. This was a moral issue. It was a matter of simple justice.

While I may have helped with the words, it was the message the president wanted to send. The force of his embrace gave them their power.

"At times, history and fate meet at a single time, in a single place, to shape a turning point in man's unending search for freedom," Johnson began. "So it was at Lexington and Concord. So it was a century ago at Appomattox. So it was last week in Selma, Alabama."

"The real hero of this struggle," the president made clear, "is the American Negro. His actions and protests, his courage to risk safety and even to risk his life, have awakened the conscience of this nation...He has called upon us to make good the promise of America." The cause of civil rights must be our cause, he continued. "It's all of us who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice...and...we...shall...overcome."

After a moment's silence, an electrical charge went through the room. In the well of the House, I tried to control my breathing. Later I heard that in Alabama King wept.

By summoning the anthem of the movement, LBJ embraced the rallying cry of thousands of young civil rights workers. The reaction signified the recognition that the president had placed the power of his office behind their struggle. Before the eyes of the nation, a great drama was playing out. The moral imperative of a social movement had become the legal imperative of the government.

In our democracy, there is tandem motion forward. Our government always lags behind an originating movement. The anti-slavery movement shaped the debate that led to the Republican Party, to the election of Abraham Lincoln and, eventually, to the Emancipation Proclamation. The progressive movement created a passionate consensus that allowed Theodore Roosevelt to pressure Congress to confront the problems of the Industrial Revolution. The gay rights and women's movements mobilized citizens, whose fight for justice led to ongoing legislative changes, civil unions and gay marriage.

So it was at Selma - the civil rights movement initiated the momentum that, together with the conviction and impassioned skill of President Johnson, led to one of the most important pieces of legislation in the 20th century. This is indisputable. I was lucky to be there, to witness Johnson at work during those months. I witnessed his fervor and determination to get it done. Far from resisting King, he worked all the avenues of power to do something with all the might and matchless skill he could muster.

The combination of Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights movement with Lyndon Johnson and the federal government created neither a black moment nor a white moment. It was an incandescent American moment.

At the signing of the Voting Rights Act in the Capitol Rotunda, President Lyndon Johnson moves to shake hands with the Rev. Martin Luther King, right. (Yoichi R. Okamoto/LBJ Library)

The Boston Globe: What the '60s can teach us about Ferguson, Staten Island today

The recent events in Ferguson, Mo., and Staten Island, N.Y., where grand juries refused to indict white police officers in the deaths of unarmed African-American men, depress me just as they depress the nation. As I've followed the news these past weeks, and having recently celebrated my 83rd birthday, my mind returns to a very different time and circumstance — the civil rights movement of the 1960s, when racial issues were at the forefront of our consciousness and when our country was moving in a progressive direction.

19 December 2014

Aspen Institute 21st Annual Summer Celebration (9 August 2014)

Richard N. Goodwin and his wife Doris Kearns Goodwin were honored at The Aspen Institute's 21st Annual Summer Celebration and presented with Public Leadership Awards for their contributions to democratic enterprise. Following an introduction by former Sec. of State Condoleezza Rice, Richard and Doris spoke with the Aspen Institute's President/CEO Walter Isaacson about their work with and study of presidents and politics. Hear their insights about Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, and more!

Click here to view the video

Richard N. Goodwin on C-SPAN Radio (6 June 2014)

Forty six years after the assassination of Senator Robert F. Kennedy on June 6, 1968, Richard N. Goodwin joins Steve Scully on C-SPAN Radio to talk about his time as an aide, advisor and speechwriter for Sen. Kennedy, and presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. Part 1.

On C-SPAN Radio, Richard N. Goodwin and Steve Scully discuss the relationship between Sen. Robert F. Kennedy and President Lyndon B. Johnson, and talk about President Johnson's overwhelming re-election victory in 1964. Part 2.

Richard N. Goodwin spoke with C-SPAN Radio's Steve Scully about coining the term and formulating the concept of the "Great Society," which Goodwin outlined in a speech for President Johnson that was delivered in 1964. Part 3.

On C-SPAN Radio, Richard N. Goodwin recalls his last conversation with Sen. Robert F. Kennedy on the evening of his assassination in June 1968 in Los Angeles, discussing how Sen. Kennedy's compassion and hard work set the groundwork for his lasting legacy. Part 4.

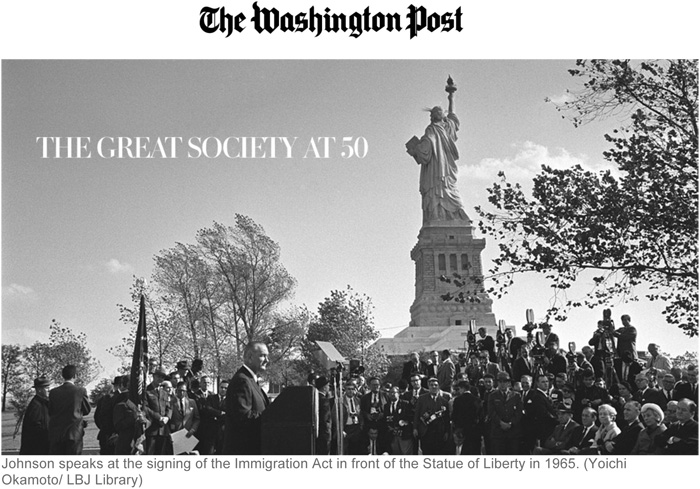

The Washington Post: The Great Society at 50

LBJ's unprecedented and ambitious domestic vision changed the nation. Half a century later, it continues to define politics and power in America.

17 May 2014

|

|

|

|